Our Executive Clinical Director, Dr. Chantelle Thomas, recently wrote a feature for TMJ4 in Milwaukee. Here she talks about how to interpret what your body is telling you and how to respond.

Dr. Chantelle Thomas, Executive Clinical Director at Windrose Recovery

Several months ago, when the sun was shining, I remember spending time with my two young daughters at the park. The girls were particularly full of energy as it had been several weeks since they had been outside. I looked on with relief and happiness while I observed a relatively “normal” moment between the two of them. Then another child entered the playground. Immediately, a rush of uncertainty washed over me. How many times can I say, “remember to give space?” Unless I literally hover over these kids it’s just about impossible to get children to maintain social distance. Meanwhile I am also trying to track the nonverbal cues of the child’s parent. Am I coming across as rude or unfriendly? Do I appear overly cautious or hypervigilant? Do I just leave the park altogether? One seemingly lovely moment is now punctuated with uncertainty, fear, conflict, and anxiety.

Several months ago, when the sun was shining, I remember spending time with my two young daughters at the park. The girls were particularly full of energy as it had been several weeks since they had been outside. I looked on with relief and happiness while I observed a relatively “normal” moment between the two of them. Then another child entered the playground. Immediately, a rush of uncertainty washed over me. How many times can I say, “remember to give space?” Unless I literally hover over these kids it’s just about impossible to get children to maintain social distance. Meanwhile I am also trying to track the nonverbal cues of the child’s parent. Am I coming across as rude or unfriendly? Do I appear overly cautious or hypervigilant? Do I just leave the park altogether? One seemingly lovely moment is now punctuated with uncertainty, fear, conflict, and anxiety.

This last year has been an incredibly trying time for so many individuals and I still have no idea how most parents coped with the virtual schooling and attempting to work. A recent survey done by the American Psychological Association found that 75% of parents could have used more emotional support than they received and mothers in particular (almost 39%) reported a worsening in their mental health. In addition to their own mental health concerns, fathers reported drinking alcohol more (48%) and gaining more weight (80%) during the pandemic. In addition to the mental health struggles, roughly half of the individuals surveyed reported discomfort in returning to “life like (it) used to be prior to the pandemic” and at the idea of returning to in person interactions once the pandemic ends.

The warm weather appears to be upon us and undoubtedly this will provide more opportunities for socialization. The world is slowly re-emerging from its cocooned isolation. Vaccines have provided opportunities to encounter situations that would have been previously avoided. For others, softening of restrictions has allowed a return to previous social habits. People are starting to travel. Some individuals are finally re-encountering extended family while others will remain separated due to various vulnerabilities or perhaps due to their opposing views of the current risk level. How do we make these decisions about what feels “safe?”

People are making decisions on what type of social interactions they are willing to do based on the available information. In this regard, one might think this is an intellectual decision determined by weighing the risks and facts. However, the experience of these choices can be largely driven by what “feels” like the right thing to do. What happens when we decide to make a choice that seems reasonable, but our body is still sending us signals that we are not safe? Can you simply decide to feel different? This answer is a bit complex and requires consideration of the role one’s nervous system plays.

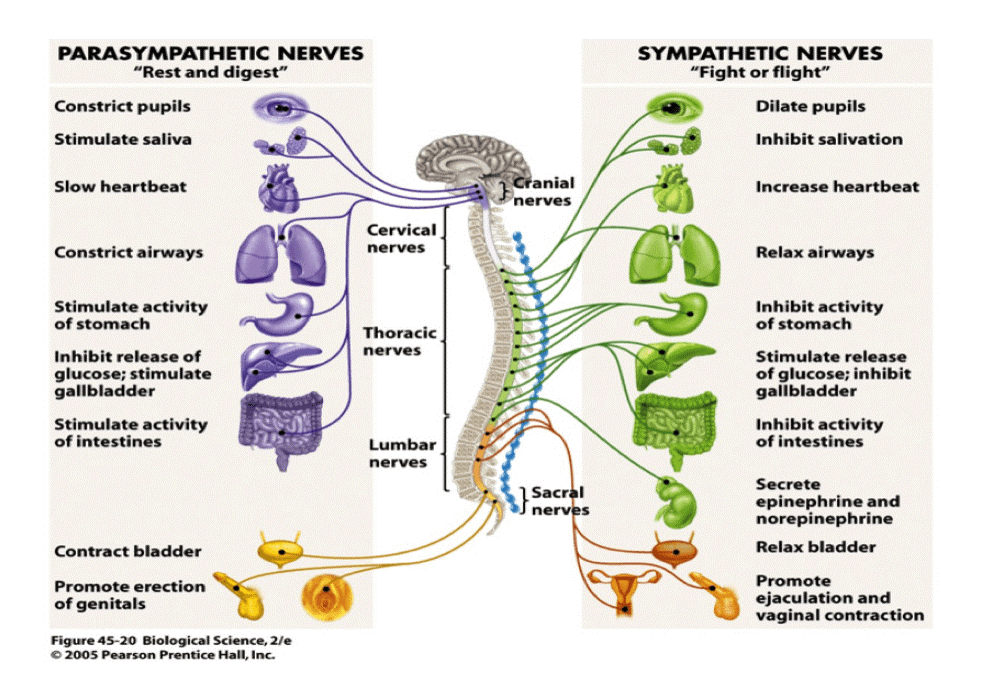

The felt sense is a raw and direct experience of the body’s feeling of a situation or memory before it is clarified into words (Gendlin, 1981). The inputs to this system are largely influenced by reflexive nervous system responses that are operating outside of conscious awareness. How are these sensations determined? By past experiences, associations, and, in many cases, an attempt to determine what is most optimal for survival. So just imagine that you spent the last year and most of your conscious waking moments thinking about how to protect yourself from a potentially fatal virus. Your body has been learning and coding the constant need for protection and the fear of encountering other people that could unknowingly infect you. The autonomic (automatic) nervous system (see graphic below) has a wonderful system of balance (somewhat akin to a gas pedal and a break) that allows for activation and arousal when needed and relaxation and decompression when we are not under threat. The activation system (gas pedal) is called the sympathetic nervous system and commonly referred to as being responsible for fight or flight. The opposing system (break) chiefly responsible for relaxation and aiding digestion is the parasympathetic system.

Over the last year, many of our nervous systems were predominantly tilted in one direction: sympathetic. Remember, this is the result of a threat reflex. How did this feel for people? The personal experience of this system being activated could widely vary from person to person. For some it was a constant state of anxiety, for others it was being “on edge,” irritable, unfocused, and/or more impatient. People did not choose to activate this system; it is an adaptive response to prepare for mobilization or fight when we sense we might be unsafe. This response does not require the conscious thought of “I’m in danger” but rather can be induced by feeling limited in self-protection and thusly vulnerable and exposed. The good news is that while most of these responses are triggered by factors outside our awareness, we do have the ability to consciously intervene to start re-establishing balance in our nervous system. We can teach our bodies that it is possible to feel safe again. How can we do this? Through our breath.

Your breath has an amazing ability to be a conscious and intentional communicator to your nervous system. When done using certain techniques, you can directly trigger a parasympathetic response which can immediately begin to counterbalance the arousal system and send messages of safety. The key is to learn how to breathe diaphragmatically (as opposed to shallower chest breathing) as this allows the activation of the vagus nerve (which automatically involves the parasympathetic system). Diaphragmatic breathing is also known as “belly breathing” and there are several tutorials online that teach this technique.

When individuals tend towards shallow chest breathing, making this transition to use your diaphragm can often be awkward, uncomfortable, and even anxiety producing. Don’t despair and remember to keep trying. Any movement towards shifting the location of your breathing can start to make an impact. Another consideration is the rate of your breathing and the way one exhales. Making an effort to be more intentional in breathing more slowly (5 to 8 breaths a minute) and deeply can be very helpful. Pursed lip breathing is a final technique that allows individuals to slow down their exhalation. This too can have very beneficial effects on the way your body uses oxygen and consequently can enhance cues for safety and relaxation.

Enhancing body awareness and using intentional tools to relearn a sense of safety can provide a critical opportunity for those who are suffering to feel more empowered and in control. Coming to the realization that we can actually make choices that directly impact the way we feel can be an invaluable way to start modifying the story being told by your body. In this regard, we can start to develop a more integrated internal awareness. This awareness of ourselves can begin to shape a coherent, compassionate narrative about how we survive and what more may be needed to thrive.

Gendlin, E. (1981) Focusing, revised edn. London: Bantam New Age Books.

Dr. Chantelle Thomas is Windrose Recovery’s Executive Clinical Director and a Clinical Psychologist specializing in addiction treatment, trauma, and health psychology. With her experience in trauma work, Dr. Thomas guides the clinical team in the comprehensive assessment and treatment of each guest. Dr. Thomas is also a certified biofeedback practitioner, providing clients with an added dimension of insight and discovery helping them better regulate and understand the psychological impact of stress and chronic trauma. Dr. Thomas began her career as the Program Director for a dual-diagnosis addiction and trauma treatment center in Malibu, California. After receiving her PhD in Clinical Psychology, she completed her internship and post-doctoral fellowship in Health and Rehabilitation Psychology at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Mental Health. While there, she gained specialized expertise in medical-surgical consultation, trauma-informed therapy and chronic pain treatment. Through the University of Wisconsin’s School of Family Medicine, Dr. Thomas then joined Access Community Health Center as a Behavioral Health Consultant to primary care physicians where she innovated the development of a substance use disorder consultation clinic embedded within primary care. Her background in research-supported treatment modalities directly informs her ability to ensure the most effective interventions are incorporated into Windrose Recovery’s holistic programs.

If you’re looking for more information about Windrose Recovery’s family of treatment programs, or are concerned about how the last year has affected someone close to you in their reliance on drugs or alcohol, reach out today to speak with our admissions team.